Game publishers seem to love a little friendly (and not so friendly) competition with each other, and we’re now about 20 years out from a rather silly arms race over which one could produce the most elaborate special edition package.

Game publishers seem to love a little friendly (and not so friendly) competition with each other, and we’re now about 20 years out from a rather silly arms race over which one could produce the most elaborate special edition package.

It wasn’t the first fancier bundle for collectors, but the bonus disc included with Halo 2‘s Limited Collector’s Edition (which was housed in a “luxurious” tin) was one of the first I remember from that era. The practice quickly escalated from those humble beginnings, and prospective players were soon being wooed with promises of night vision goggles (Call of Duty: Modern Warfare), drones (Call of Duty: Black Ops II), a Batarang (Batman: Arkham Asylum), so many wearable helmets (Doom Eternal and Mass Effect, to name just two), and even a statue of a bloodied and bikini-clad torso (Dead Island: Riptide).

This retail trend has mostly run its course these days, but not before Volition tried to sell Saints Row fans on a one-of-a-kind “Million Dollar Pack” for Saints Row IV. The ridiculously over-the-top bundle included multiple cars and trips, as well as admission to a spy training school, and a voucher for plastic surgery. While obviously a parody of all the weird and wild special editions mentioned in the previous paragraph, I’m sure Volition would have tried to mass-produce the “Million Dollar Pack” if anyone had offered to buy it.

Publishers definitely went a little overboard chasing this fad, but it was more or less an extension of the old “Big Box” releases that would often include a world map or a small trinket with a highly-anticipated game. Let’s look at three of those bundles in this edition of Bite-Sized Game History…

![]() You can find a lot of dedicated video game historians on Twitter, and in 280 characters or less, they always manage to unearth some amazing artifacts. Bite-Sized Game History aims to collect some of the best stuff I find on the social media platform.

You can find a lot of dedicated video game historians on Twitter, and in 280 characters or less, they always manage to unearth some amazing artifacts. Bite-Sized Game History aims to collect some of the best stuff I find on the social media platform.

While most special edition packages are designed to separate fans from a slightly larger portion of their cash, not all of them were available to the general public. For a great example, look at the Swag Kit given to journalists as part of Electronic Arts’s marketing plan for the launch of The Godfather II in 2009.

The first game based on Francis Ford Coppola’s film was well-received, but the publisher wanted to add a little punch to their promotional activities for the sequel. That something extra took the form of a real set of brass knuckles, which was included with most review copies of the game. There was just one problem with this gift… brass knuckles were (and still are) illegal to own in more than a dozen states. And in Electronic Arts’s home state of California, it’s against the law to even ship a set of brass knuckles through the mail:

'electronic arts sent out brass knuckles to game journalists as part of its promotional kit for the godfather II.' (2009) https://t.co/WsKhWnSt3c pic.twitter.com/Zqjf0Elq5X

— weirdo (@vg_history) January 2, 2022

Game developers have always been enamored with bugs. You can see it in the retro thrills of Yars’ Revenge to the Heinlein-esque big bugs of the Earth Defense Force franchise to the the over-the-top extermination methods of Kill It With Fire.

But none of those games can measure up to Infocom’s The Lurking Horror from 1987.

The decade’s premier publisher of text adventures was well-known for including real-world objects with their games. These “feelies” operated as a rudimentary copy protection system, as well as a way to give the text a slightly more tactile flavor. And the package for The Lurking Horror, which was recently shared by Florencia Pierri, was certainly one of the most memorable.

That’s because this absolutely gruesome centipede was waiting to give players a shock when they opened the box. And unlike the rest of the bonus items, the giant bug was not pictured on the back cover:

Today at work a fake bug scared the crap out of me. Thanks, Infocom! This was an accessory (called a feelie) for the computer game The Lurking Horror. Since Infocom games were all text-based, they included 3d objects in the game packs that related to the game play at some point. pic.twitter.com/rm1ZeR6ixi

— Florencia Pierri (@_fl0ri_) July 15, 2022

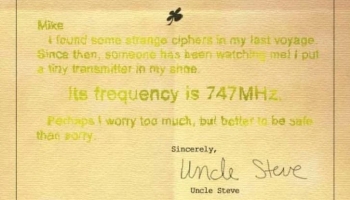

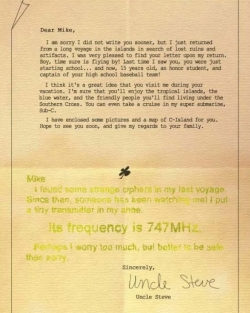

Petering out after just a pair of games, StarTropics is one of Nintendo’s many forgotten franchises, but the NES action-adventure still has a lot of fans in 2022. While most fondly remember the Zelda-like gameplay, others still get a little kick out of the real-world letter that was needed to solve one of the game’s earliest puzzles.

StarTropics put players in the baseball cleats of Mike, a typical American teenager, who had travelled to the tropics to visit his Uncle Steve. But his vacation on C-Island was cut short before it even began by an alien invasion. After commandeering his uncle’s submarine, the resourceful teen fought giant sea creatures and escaped from the belly of a whale in the search for his uncle. It was exciting stuff, but players who wanted to continue past StarTropics‘s fourth chapter needed to give a secret numerical code to the sub’s navigation robot.

According to one of the game’s characters, the code was hidden somewhere in the letter, but there weren’t any numbers on the paper. The only way to proceed was to dip the letter in water to reveal a secret message written in invisible ink. Sounds easy, right? But the letter was rarely circulated with rental copies of the game, and even Nintendo has had a spotty history with preserving this cool feature in StarTropics‘s subsequent digital re-releases.

The best digital representation of the letter is the small animation found in the Wii re-release. Pressing a button in the Pause Menu would dip a virtual piece of paper into a virtual bucket of paper and then display the code on the screen.

The letter is also included as part of a scan of the instruction booklet on Nintendo’s official website, but the secret message isn’t visible. This mistake was rectified for the Wii U re-release, which included a new scan of the letter with the secret message visible.

But for the Switch re-release of StarTropics, Nintendo didn’t include any way to access the letter within the Switch Online app, rendering the game impossible to complete without outside help, as seen here in a recent post from TokenAttraction:

DYK that in the digital conversion of the StarTropics manual, the code for Chapter 4 wasn't carried over?

During the digitization, all pages (+letter) were published, but bc of the paper used, the secret wasn't visible. It was on the Wii U VC that this was fixed. pic.twitter.com/hTQfyun5Ok

— TokenAttraction ? (@TokenAttraction) June 21, 2022

Thanks to @vg_history, Florencia Pierri, and TokenAttraction for the tweets from this edition of Bite-Sized Game History. And you can follow me on Twitter for more out-of-the-box ideas.